Menu

- Undergraduate

- Exchange Program

- Research

- Equity

- News & Events

- People

- Contact us

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Recent article in the New York Times by David Leonhardt reference Friedman, Sacerdote and Tine SAT data from the entering classes of 2017 to 2022, excluding 2020.

New York Times, January 8, 2024

Good morning. We're covering the debate over standardized tests in college admissions — as well as Israel, artificial intelligence and the Golden Globes.

Higher education has a standardized-test problem, and it's not the problem that many people think.

During the pandemic, dozens of colleges dropped the requirement that applicants take the SAT or ACT. Although administrators generally described the move as temporary, most colleges have since stuck to a test-optional policy.

But the loss of SAT and ACT scores has become a problem, administrators have told me. Without test scores, admissions officers sometimes struggle to distinguish between applicants who are likely to thrive at selective colleges and those likely to struggle. Why? Because high school grades do not always provide enough information, especially because of grade inflation in recent years.

As Christina Paxson, the president of Brown University, recently wrote recently wrote, , "Standardized test scores are a much better predictor of academic success than high school grades."

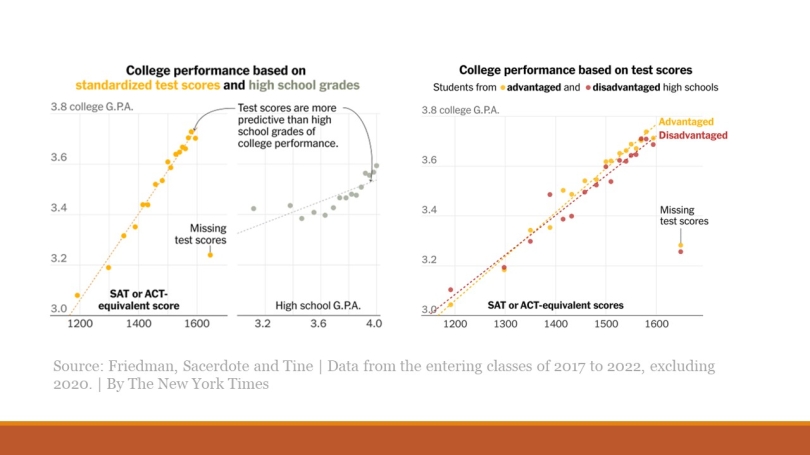

Consider the below chart by my colleague Ashley Wu, based on data from some elite colleges that academic researchers at Brown and Dartmouth released last week. As you can see, standardized-test scores predict college grades more accurately than high school grades do:

I understand why many people dislike standardized tests. They're unpleasant to take, and they have their flaws. The most significant concern is that they may be racially and economically biased.

But the emerging data from academic research tells a different story: Standardized tests are less biased than many other parts of the college application process, like extracurricular activities, college essays and teacher recommendations. An admissions system that drops mandatory tests in favor of these other factors gives big advantages to affluent students.

Test scores, by contrast, seem to be useful at identifying students from disadvantaged backgrounds who have enormous potential, even if their scores aren't quite as high on average as the those of well-off applicants. "When you don't have test scores, the students who suffer most are those with high grades at relatively unknown high schools, the kind that rarely send kids to the Ivy League," David Deming, a Harvard economist who has studied the issue, told me. "The SAT is their lifeline."

Here's another chart, which separates applicants by advantaged and disadvantaged high schools, and shows that test scores are not simply a proxy for income or race. Advantaged students who do better on the SAT or ACT do better in college, and the same is true of disadvantaged students:

[A chart showing college performance based on test scores from students from advantaged and disadvantaged high schools.]

Source: Friedman, Sacerdote and Tine | Data from the entering classes of 2017 to 2022, excluding 2020. | By The New York Times

The Times recently started a new feature called Ideas, in which our journalists try to go deep on a major subject. I wrote this week's installment this week's installment, about standardized tests. As part of the article, I describe what happened after M.I.T. became one of the few colleges to reinstate their test requirement.

Tests scores are not the main factor that M.I.T. uses, but they are part of the process. "Once we brought the test requirement back, we admitted the most diverse class that we ever had in our history," Stuart Schmill, the admissions dean, said. In M.I.T.'s current first-year class, 15 percent of students are Black, 16 percent are Hispanic, 38 percent are white, and 40 percent are Asian American. And M.I.T. is more economically diverse than many other elite schools.

In reporting the story, I came to think of it as a parable for our politically polarized society — and for what happens when empirical evidence contradicts many people's initial instincts. Responding to the article in a tweet yesterday, Melissa Kearney, a University of Maryland professor, wrote that standardized tests had become "another policy instance where doing what 'feels good' turns out to be counterproductive."